Stonehenge and Hippies

by Gary White

It was 1972 and I was in a rental car driving around rural England in search of a pile of large rocks. I had heard that Stonehenge was an important prehistoric site and added it to my list for the road trip.

Stonehenge wasn’t easy to find. I had a map that showed its location in the middle of a cow pasture on an unpaved country road. Seeing a group of standing stones in a field, I parked alongside the road. I carefully climbed over the barbed wire fence and crossed the cow-patty-sprinkled pasture. A herd of cattle grazed in the distance. As I approached, the stones loomed larger and larger. Huge grey archways towered twenty feet over my head, much taller than they had appeared from the road.

I was met at the stones by an elderly man in a worn grey National Trust uniform and cap. He had a sheaf of papers and proceeded to tell me what he knew about the site, which he dated to approximately 2,000 to 3,000 BCE. We leaned against or sat on the stones while he talked, and he used one of the recumbent stones as a makeshift desk on which he spread his papers. He explained that the site is thought to have been used for ceremonies and rituals—a kind of megalitic temple, and that it had been rebuilt several times over a period of more than a thousand years. We had the site to ourselves for the hour he took to make his presentation.

It was impressive to stand in the midst of those 20 to 30 ton stones and learn that people 5,000 years ago carried them there from a great distance and erected them. We still don’t know how they transported some of the stones over water. I went away with a new respect for our ancestors. I also made a mental note that someday I would show this site to my family.

“Someday” came about eight years later. Again I had a rental car, but this time I had my family with me. We drove up to the site and I discovered it had changed. Instead of cow patties and barbed wire there was a parking lot, a small visitor center, and a marked trail that crossed the road and led up to the stones. Stonehenge was now an official National Trust attraction, managed by English Heritage, with entry fee, gift shop, and plenty of uniformed staff.

We walked up the trail to the standing stones. I was shocked to find that they had encircled the stones with a chain-link fence, and no one was allowed in. My kids stood with their noses and fingers in the holes of the chain-link fence, with longing in their eyes. I, their parent, longed to be able to give them the experience I had had just eight years earlier. The stones were only ten feet away—but untouchable. What had changed everything? Hippies, that’s what.

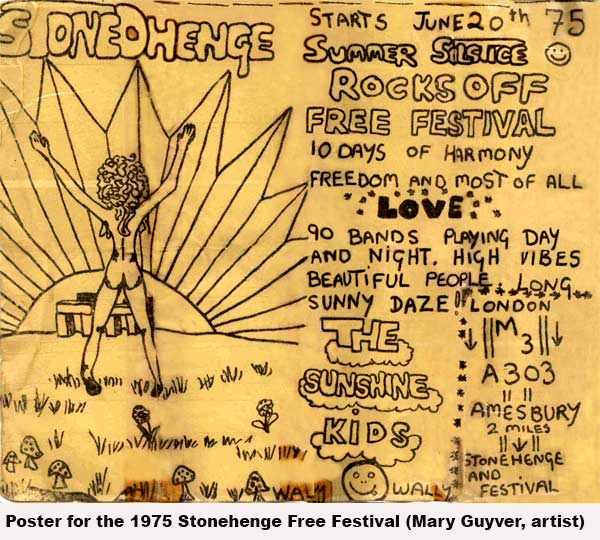

In 1974 a counterculture group decided to host a free music festival at Stonehenge around the summer solstice. The Stonehenge Free Festival, which ran from 1974 to 1984, attracted the ire of the more conservative elements of British society and they decided to put a stop to it. After many attempts, including erecting that awful chain-link fence, they succeeded. But by then, perhaps in part because of the notoriety the festival had generated, Stonehenge had become a huge tourist attraction. And tourist attractions have to be managed. In any event, I derive some private satisfaction from thinking that those weed-smoking, drug-dealing hippies of my generation may have actually helped to popularize Stonehenge.

I’ve been at Stonehenge several more times—most recently in 2014—and every time the set-up has become more elaborate and more controlled. Access is ever-more limited. The new visitor center about a half-mile away from the stones is filled with all sorts of high-tech media displays, but they have closed off the road that ran by Stonehenge. Special busses now ferry visitors to the stones, which can no longer be seen from the visitor center.

I rode their special bus with a tour guide talking constantly on the intercom system. I was grinding my teeth all the way at his inane commentary.

Even though the chain-link fence is gone, there is a low fence and plenty of watchful security guards, so you still can’t walk among the stones. A new, concrete walkway circles the site at a respectful distance. “Look, but don’t touch” seems to be the motto. English Heritage appears to be trying to give tourists a “Disneyfied” multimedia experience while minimizing actual contact with the stones themselves.

If you want to pay an additional fee and schedule well in advance, you can join a special group tour to walk among the stones before or after regular open hours. I’ve done that twice, once to be at the stones at sunrise, and once at sunset. There were guards everywhere making sure that we didn’t so much as accidentally brush against one of the stones. The feeling of being watched with suspicion made me uncomfortable, and the babble of competing tour guides made it difficult to be “present” to the sacred site. It was great to be among the stones again, but I couldn’t help remembering what it was like in 1972 when it was just me and that ancient guide with his makeshift maps.

For years I have been outraged at how people are being kept away from the stones. I’ve often complained, “Just what are the powers in control trying to protect, anyway? Twenty-ton stones are unlikely to be damaged by a slight touch.” But something I learned recently has made me question my opinions. An archaeological study reports that the original builders may have erected a 20-foot-high palisade of wooden poles alongside the stones. Its sole purpose was probably keeping those not in the priestly or ruling class from viewing the site and the ceremonies being conducted there. Maybe English Heritage is just returning the site to something closer to its original state! Maybe my experience in 1972 is the one that was an abuse of Stonehenge, not the exclusionary tactics I’ve recently witnessed.

Gary White blogs at www.FandangoLife.com. Together with his wife, Elyn Aviva, they write and publish a series of guidebooks with the general title of “Powerful Places in . . .” (www.PowerfulPlaces.com)