Finding My Father

By Cliff Simon

Three months after my Bar Mitzvah in March 1964, I was wandering in my synagogue on a hazy and humid Saturday morning, searching for a lone seat among the pews, when I noticed a group of old Jewish men huddled together, talking in the back of the sanctuary. With my heart pounding, I was certain they were discussing me, whose father was buried a few weeks earlier, on his 51st birthday. I was thirteen but looked more like ten, a scared chubby Jewish boy wearing a Talis, who had just lost the father he never really knew.

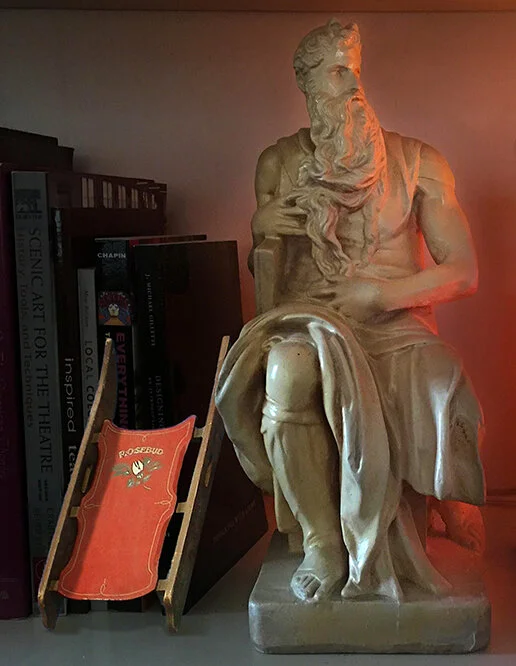

He was a learned, teenage peasant immigrant from Poland, whose Slavic name was changed to a more American sounding one in Warsaw before he boarded the boat to America. When he arrived, passing through Ellis Island in the early 20th century, his name had been transformed from Moyshe Sýkora to Murray Simon.

I think of him crossing the Atlantic. It is a distressing narrative of the person who was always an enigma to me. He was carried on the crest of a wave. Aided by a strong wind, it held no concern for his consent or welfare. He was deposited without the warmth of a welcome onto this foreign soil, suddenly Mr. Simon.

It was difficult for him to adjust here. He was not, in the eyes of this world, a successful man and I imagine his quiet, religiously devout, eastern European sensibility was somehow out of step in a place where people had to adapt, shift gears, stake a claim and leave a legacy which reflected their integration into America. My father had no such ambitions; he had never worked for anyone but his father, and here he opened a used furniture business in Harlem, a one-person operation that each year became increasingly less profitable.

My mother, the woman he fell deeply in love with after he arrived, had expectations of upward mobility, and I’m not sure he ever thought about such things. As much as they truly loved each other, they had difficulty understanding each other’s reality, wishes and dreams. She couldn’t change what she wanted, so, like many other wives, she altered the situation instead, and went to work in the 1950s to bolster the family income. Resentment slowly festered inside of her, and the pressure of her needs became oppressive and threatening to my father. Their increasingly divergent perspectives quietly gnawed at the edges of their happiness, and they were unable to find a solution.

Somewhere in my mind, I believe that the cancer he developed was caused by his helplessness to give the woman he loved what she needed. He died two days after his subsequent heart attack, which at least allowed him to physically suffer less than the cancer that was consuming him. Perhaps this is not a story for a romance novel, yet, for most of my life since he died, I found myself admiring him. He remained pure, in his own way, and in the fact that he wasn’t willing or able to fully let go of the life he came from, I saw strength of character. One could say he might have made the wrong decision by emigrating here, but had he stayed in Poland he would surely have died in Auschwitz. When all is said and done, he built a life enveloped by the warmth of family. Everybody loved my father, though I’m not sure how many really understood him.

As I approach seventy, I see that my face resembles his, and I wonder if I have inherited his lack of ease in this world and his feeling of being out of place and frustrated that things always seem to be a struggle. Did he ever think about such things, this soft-spoken man who deftly protected his emotions and never expressed his inner thoughts?

When I was eleven, my father and I went outside to play catch. We had never done that before. Or ever again. I know it had to have been at my mother’s prompting. It wasn’t terrible, nor was I as frightened as I thought I’d be, and it didn’t last long. After we finished we went inside, having both done our duty. I’ve thought about that catch over and over since I was a kid, visualizing it in my mind, observing it from above like from a drone, looking down at this special event, wondering if he felt as awkward as I did, as we were doing something together that was out of character for both of us.

Back then, neither of us had any idea of who the other was. We were a father and son on two ends of the universe, speaking different languages. After he was gone, though, I began to realize the grace and poetry of our relationship. Like the similarity of our two faces, we shared an unwelcome alienation of a world that frightened us and stopped us in our tracks. In our own way, we each sought a path to find our peace. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, I can empathize with this man who is my father.

So many times I’ve imagined that if I were the only person on an island, I could finally breathe freely, without feeling like I have to be what everyone else wants of me. I know he would have understood that. And though I cannot hold him, hug him, sink my head into his shoulder, I can feel the warmth of his breath on my skin and the beauty of his soul in my heart.

Cliff Simon has designed hand-painted cakes since the late '70's, in New York, San Francisco, Austin and Santa Fe. Presently he teaches Scenic Design at UAB, designs at regional theatres and continues to bake, paint and write, the medium that has always helped him better understand life. Learn more at http://www.cliffcakes.com