How Exposure to Indian Art Taught Me to Love My Body

By Noor Anand Chawla

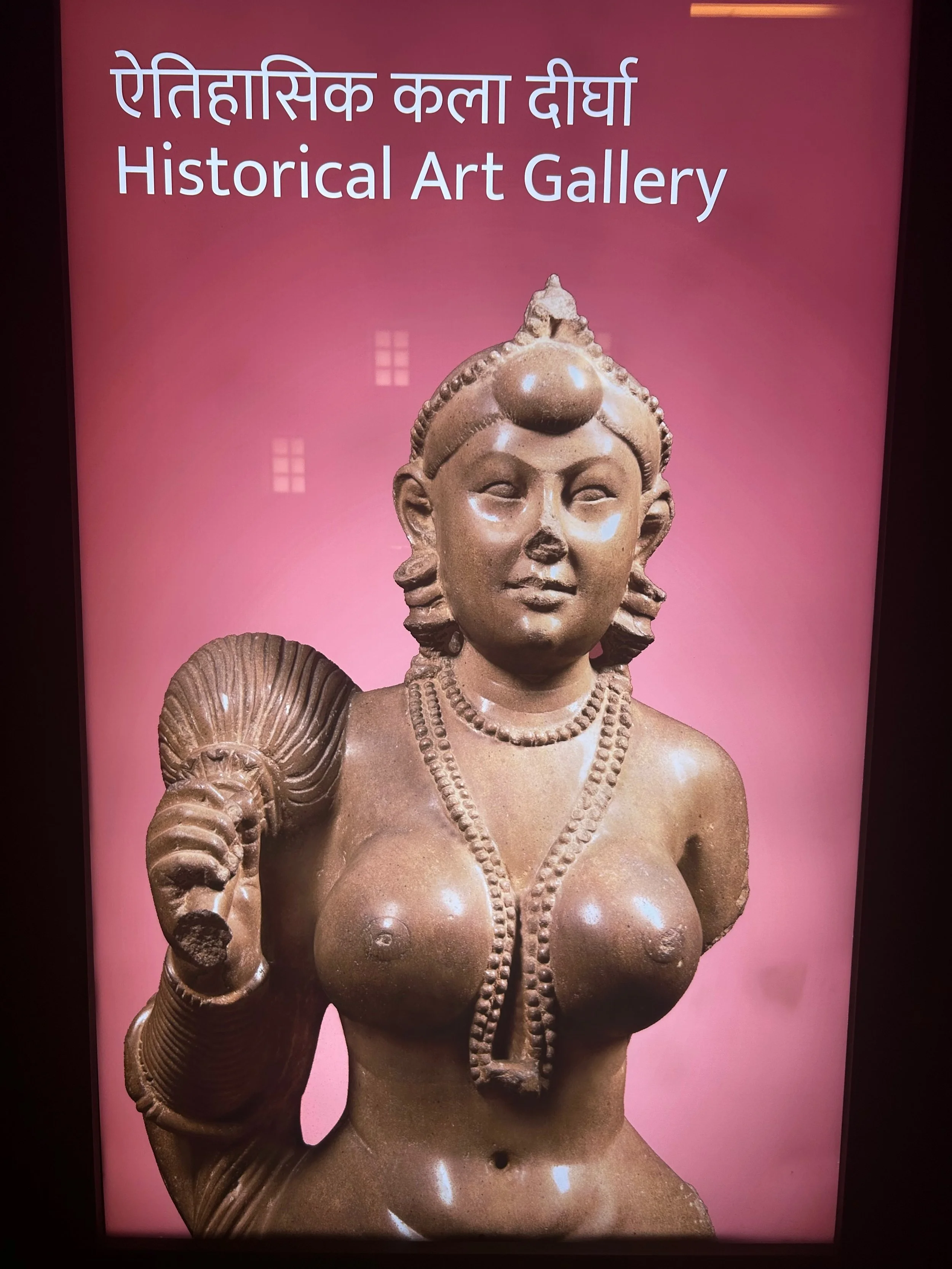

“Have you seen the Didarganj Yakshi? She’s absolutely stunning! She outshines the Mona Lisa by a mile!” said a fellow delegate as she walked out of the historical artefacts gallery at the Bihar Museum in Patna, Bihar. We were part of the media crew attending the two day opening ceremony of the Bihar Museum Biennale 2023, and she was referring to the most famous exhibit in this new-age museum which houses a large collection of ancient artefacts discovered during the British reign, as well as a growing contemporary art collection.

I eagerly turned to the statue to verify this claim and discovered that she was right. The Yakshi was definitely a stunning work of art. While I examined the smooth folds and curves of her exquisite figure, I pondered on my own misplaced body dysmorphia. As a medium-sized curvy girl from India, I have struggled with weight-related insecurities all my life. Yet comparing my figure to the Yakshi made me feel empowered.

To examine the root of this problem, a glimpse into India’s history is in order. After the British colonisers departed in 1947, our country chose to follow a socialistic regime where the rigid controls of government curtailed global exposure. India opened its economy to international private players only in the 1990s, and children of that decade began inadvertently believing the western narrative to be the worthiest. Hence, the stick-thin supermodels of the west quickly became figures of beauty to aspire towards. They were tall, statuesque, mostly light-skinned, and possessed a hangar-like quality that would put most mannequins to shame.

My modest 5’4” well-endowed hourglass frame was in stark contrast, but I held these slender beauties in high regard and tried my best to emulate them. This led to years of yo-yo dieting, where I would consult self-styled “nutritionists” who would prescribe extreme diets that would help me shed a few pounds and look slimmer. But as soon as I returned to a normal diet, the weight would come back, making me feel sad about my appearance. And the rigmarole would begin again.

It was silly. I knew I was never going to fit these European beauty standards, but I doggedly kept trying. Over time though, I became resigned to being “pleasantly plump”, to quote an old English phrase. I didn’t like it, but I made peace with it. Then as I gazed upon the beauty of the Didarganj Yakshi, I felt strangely empowered. Her voluptuous frame was more like mine than any skinny beauty from the west – and she was undoubtedly beautiful!

The Didarganj Yakshi is a work of stone masonry dating back to the 3rd century BCE that is presumed to have been commissioned by the kings of the Mauryan dynasty. It is the statue of a heavenly sprite found in the area of Didarganj in Bihar, a state in eastern Indian. The statue stands at an impressive height of 5'2" and is sculpted out of smooth and shiny slate-colored Chunar sandstone. It has been dated to this period owing to its highly polished stone and detailed finery, natural posture and large scale, which are signature elements found in other Mauryan sculptures.

It is believed that Yakshis were spiritual beings, worshipped for their role in the promotion of fertility and prosperity, as evident from their full figures and happy and self-assured demeanour. The Didarganj Yakshi was discovered in 1917, buried deep inside the banks of the river Ganga, where her foundational stone was being used as a slab for washing clothes. Despite this misuse and the ravages of time, she remains a fine example of religious art, with the lustrous polish of her stone still intact.

The Yakshi’s stance mimics a natural one, as she stands with her weight resting on one knee and the other gently bent. As a consequence, she leans forward much like a person in that state would. Her facial features are delicate and beautiful with arched brows framing large almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, and an alluring pout. She wears a silky garment to cover her legs, leaving her ample bosom, small waist and rounded stomach completely bare. The only adornment on the upper part of her body is her beautiful jewellery – long strands of necklaces, large earrings and a round ornament that rests on her forehead. On her right arm she carries a fly-whisk. The only disfigured parts are a missing nose and arm.

Her finely-carved figure provides a valuable record of the idealised female form in this part of the world. She is a voluptuous woman with large well-shaped breasts, a tiny waistline and curvaceous hips – far removed from the waif-like appearance of models of the modern era. Musing upon the similarity in our figures, I examined the folds on her lower abdomen which mirror the ones I acquired after giving birth to my child.

As an ordinary person, I cannot lay claim to her perfection of form, but I did feel more attuned to her figure than to those I see in the media today. I felt empowered in my identity as an Indian woman and fortunate, perhaps for the first time in my life, to be gifted an ‘Indian’ figure by nature and genetics. Does this mean I am rid of my insecurities? No, as those are too deep-seated to be shrugged off easily. But I do feel less alone or ‘othered’. The next time I find myself hiding behind a large and loose outfit or sucking my tummy in while looking at myself in a mirror, I will think of the Didarganj Yakshi and be more forgiving of myself.

Noor Anand Chawla is an independent lifestyle journalist from New Delhi, India. Her work has been published in CSMonitor, ARTNews, JStor Daily, Glam, and many other publications of note. She blogs at www.nooranandchawla.com and creates visual content on Instagram @nooranandchawla.