If you travel to the Philippines, where singing is a national pastime, American expat B.J. Stolbov advises you to let go of inhibition and join the fun.

All tagged living abroad

Deejaying in Taiwan

With a typhoon raging outside, the dance floor was jam-packed with a mix of Taiwanese and expats, grooving under a musical trance on All Hallows’ Eve. It was 2005 and deejay Chris Pady was slinging just the right infectious beats to rule the room. It was heady stuff, complete control, a superpower that today lies mostly dormant until he hears La Lupita and immediately he's thrown back to a time when he ruled the world.

We Are All Immigrants

As an American expat teaching English in high schools and universities in the Philippines, YourLifeIsATrip.com contributor BJ Stolbov's students often ask him, “What makes Americans American?” Learn why it's a question that he finds difficult to answer as America becomes increasingly socially and politically divisive and discover how his answer is still one that unites.

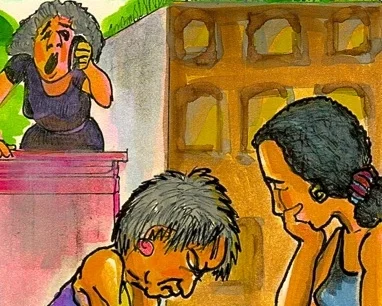

Locked Out in Mexico

An old lock breaks on the front door of a Mexican casita, trapping the cleaning woman and a high-strung woman inside with writer/illustrator Jan Baross locked outside. The fun really begins when the woman panics and jumps onto the neighbor's roof and practically the entire barrio becomes involved in the search for a locksmith to free the captives.

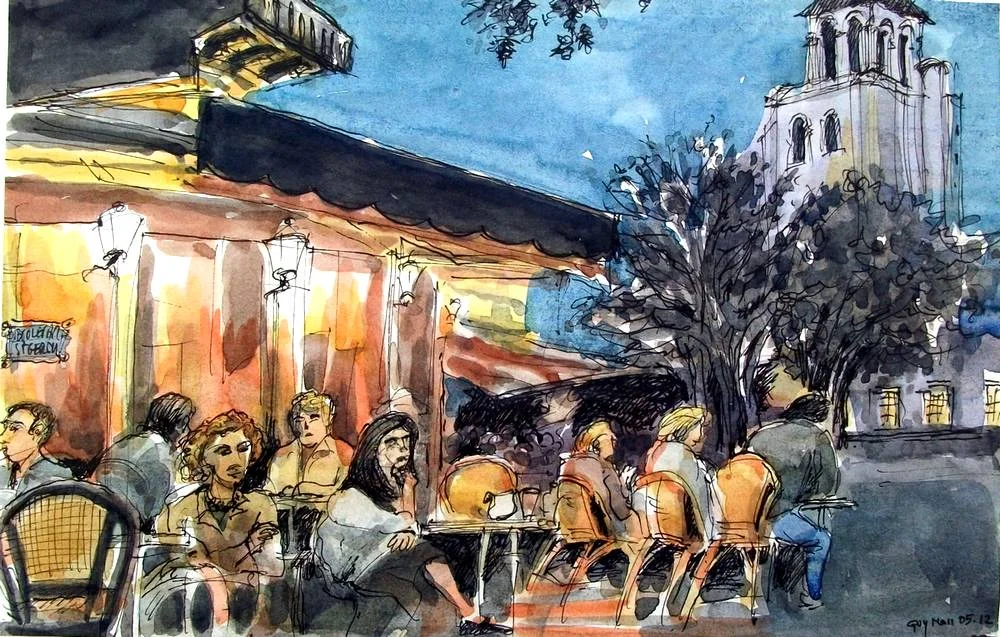

Mastering the Art of French Dining

by Dorty Nowak After growing up in a family where dinner was eaten off trays in front of the TV, I wanted to create a gracious dining atmosphere in my own home. Lit candles and cloth napkins were the norm, and I combed Good Housekeeping for tips to better the ambience for my family and guests. However, it wasn’t until I moved to Paris that I discovered how little I knew about what truly makes a pleasurable dining experience.

Driving In France

Nervously, I edged into traffic and was, within a few minutes of breath-holding, relieved by the minor miracle of finding a free parking space in front of a cafe. I sat down with my iPhone to map a plan for the week.

In search of sun and warmth, my idea was to head for the Mediterranean beaches but was told it would be very crowded in July, and the distance seemed too far – 8 hours on expensive autoroutes. So I convinced myself to keep it simple on the first day and headed to Beaune, the "wine capital of Burgundy," less than two hours away by toll road.

Mama Arli’s Due Date

“Na! Na! Hurry; let’s go to the market! Ayo!” Mama Arli’s raspy voice bellows below my kitchen window.

Mama Arli is my neighbor four houses down from mine, and she is always yelling at me. She’s pregnant with her third child, though hardly showing. Arli is the name of her firstborn son, and his name replaced her own once he was born. All mothers are called by their firstborn’s name without exception.

Her house is sturdy, also on stilts, and she is fortunate to have a deep well located just a few feet from her kitchen ladder. It is November in Indonesia and this means its coffee-picking season for those in our Sumatran village. Mama Arli and her husband aren’t home much; instead they are occupied with the daily task of harvesting beans, and then drying the beans on tarps beside their home.

Thoughts on Happiness

Living in a foreign country is an opportunity to learn about a different culture, a different way of seeing and responding to the world. It provides an opportunity to immerse yourself in new customs and traditions, and to see what really matters and is important to people around the world. It is also an opportunity to examine, from a distance, your own customs and traditions and, most important, your own cultural assumptions.

What If We Didn't Go Home?

“So, when exactly are you coming home?” my father asked.

“I don’t know, Dad. Our visas allow us to stay in Peru for at least three months, then we’re thinking of heading on to Argentina and Chile...”

The broken and sputtering magicJack connection at the South American Explorers Club in Cusco broadcasted about every third word of our conversation, but the message that traveled down the steep stone streets of the ancient Inca capital and across the continents to the lush green lawns of Newark, Delaware, the college town I’d grown up in and where my parents still live, was crystal clear: We weren’t coming “home”.

The truth was, my husband, Hank, and I had no idea when, or if, we were going home. We didn’t even know what “home” meant anymore. We’d been winging it, temporarily inhabiting Mexico, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Peru: itinerant and loose in the world in a manner that both worried and intrigued family and friends back home.

We were four thousand miles from our homeland, eleven thousand feet above sea level, south of the Equator where summer is winter, and living in a fourth-floor walkup without heat. Yet, life felt sweet and rich and fortunate.