My wife, Michele, and I spent much of our twenties in one of Taiwan’s lesser known cities, Tainan, where we soaked up the former capital’s unique culinary, social, and cultural delights. Food and rent were cheap while teaching wages were high. Meeting friends for a lavish feast on a whim was practically the norm.

All in cultural immersion

At the Bathhouse in South Korea

by Dina Lyuber

Being naked in public, for a North American, is the stuff of nightmares. Why? Is it because our bodies are so embarrassing? Perhaps it’s just a social convention; we are expected to hide our bodies, and so we feel awkward in public spaces when we must expose them. Maybe this is why many tourists avoid bathhouses. After all, they have a perfectly nice, private bathtub in their hotel room. And back home, they can wear a bathing suite as they sink into the hot tub at the community pool.

They may have avoided exposure, but they have no idea what they are missing.

Farewell to the Highlands: Pisco Sour to the Rescue

by Angela Smith Kirkman

“Meet us at El Embrujo in 30 minutes,” the voice on the other end of the line says in Spanish.

“Gloria?”

“Yes, I’m here with Marlith. We’re sending a taxi to pick you guys up. It’s your last night in Peru—our last chance to boogie down.” [My translation.]

“Thanks for the invite, Gloria, but I’m sorry, we just can’t do it.” I say, glancing toward my husband, Jason, who’s busy making sure all of our passports are in order.

I still haven’t quite figured out how to dance to Peruvian pop music, but I’m giving it my best shot.

Road Kill

Mageru pulls over to the side of the road, parks and idles the Land Cruiser. We are still a few hours away from arriving back in Addis Ababa. He looks over to me, pats the steering wheel and says “I am a little tired. You can drive.”

This does not strike me as a generosity I should accept. Although I am confident in Canada, Ethiopian driving doesn’t exactly rev my engines. “Oh…I don’t think so, honey. The driving here is very different from my experience back home.”

Fishing for a Future

by B.J. Stolbov

When I was young, my father took me on a father-son bonding/camping/fishing trip to some unpronounceable lake in upstate New York. I learned to squeamishly poke a hook through a wiggling worm. I learned to awkwardly cast a fishing line out into the lake. And when I did catch a fish, with the point of the hook sticking out through its eye, I immediately learned, while screaming and crying, that I was no fisherman. No fisherman either, my father and I gratefully agreed to bond by never going fishing again.

Street Tango in Buenos Aires

by Kate McCahill

On weekends, Alex and Vicky, my landladies, take me on walks through Barracas and San Telmo. They have known these Buenos Aires neighborhoods all their lives; they point out old buildings they’ve inhabited and the places where grand old cafés once stood. They are sisters. They’ve each been exiled twice, the first time to Europe for political reasons, the second to Mexico for economic ones. Each time, they returned because things were improving in Argentina, and they wanted to be a part of the change. They’ve rented their spare room to dozens of foreigners over the years, English teachers and language students like me.

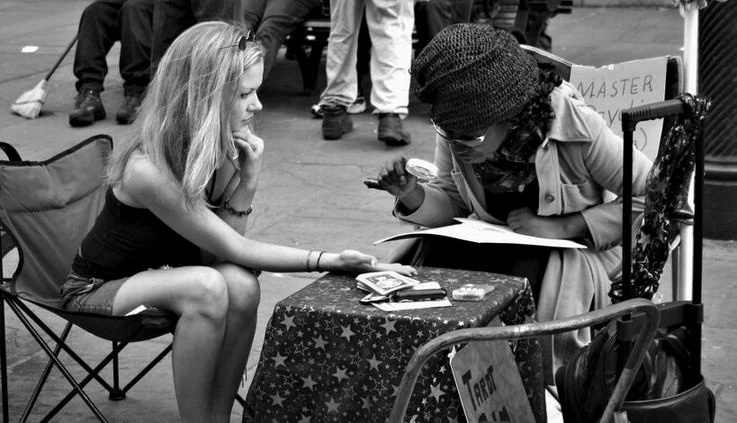

A Psychic’s Prediction of Love

I was 22 when a friend persuaded me to see a psychic in my home town on New Zealand’s west coast. At the time I was studying science and psychology at university, so I told myself psychic predictions were fanciful. But I was curious too. Like most young women, I wanted to know when I would meet the man of my dreams.

by Dan Dworkin

What would you do if you were asked to voluntarily give up your cell phone, computer, TV, and sex for a month? When I revisited my Peace Corps assignment after forty-two years away, the people of my village in Fiji, indeed the residents of the whole province, were doing just that, in a manner of speaking. They were giving up tobacco, yaqona (kava), their ceremonial drink, and sex for a month. Why would they do such a thing?

One hundred and forty years ago, the people of a nearby village, Nabutautau, killed and ate the Methodist Reverend Thomas Baker. When I visited in July, 2011 they were conducting a ceremony of reconciliation, begging the Methodist Church to forgive them for their ancestors' actions.

Making History at Frommer’s

by Edie Jarolim

It is 10am and I am sitting in a tiny mid-Manhattan office, contemplating penis sheathes. I'm not talking about the latex variety, though my fantasies of spontaneous, sweep-the-papers-off-your-desk sex always end with concern about sexually transmitted disease.

Homeward Bound

by Angela Smith Kirkman

As far back as I can remember, my life’s goal has been to travel around the world. Now, as I sit in row twenty-two of our Boeing 777, chasing the moon over the Pacific somewhere between Tokyo and the International Date Line, I can feel the book closing on this chapter, on the whole epic adventure. And the same question keeps resonating in the back of my mind.

Temazcal Sweat Lodge in Cozumel

by Fyllis Hockman

I am sweating profusely. My pores are so overrun with liquid that I fear I will float away in a river of my own perspiration. Since I am molting inside a sweat lodge, I figure I can’t go very far. Temporarily reassured.

“It’s A Blessing!” A Filipino Wedding

On a sunny dry day, about an hour before the wedding, it begins to rain; the skies open up, dumping torrents of tropical rain, and I say to the family of the bride, “I’m sorry about the rain.”

“It’s a blessing!” they reply.

An hour later, it’s again sunny and dry, and outside the church on the island of Mindoro in the Philippines, the bride is waiting, dressed in her full wedding gown, inside an air-conditioned van.

“It’s a blessing!”

The groom is waiting outside the church, in the increasing heat; he is spotlessly clean and his hair neatly combed.

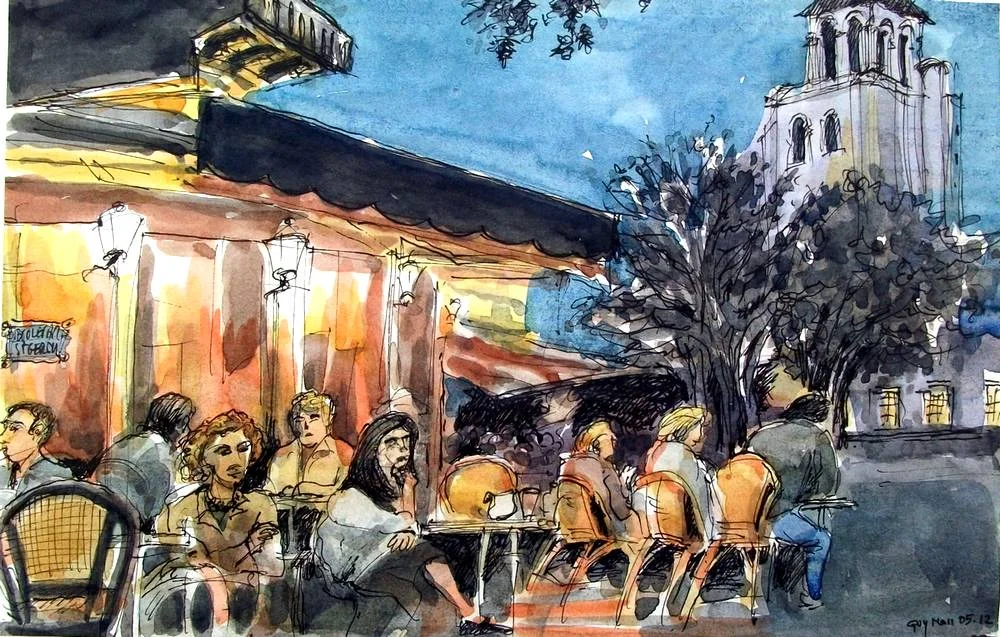

Mastering the Art of French Dining

by Dorty Nowak After growing up in a family where dinner was eaten off trays in front of the TV, I wanted to create a gracious dining atmosphere in my own home. Lit candles and cloth napkins were the norm, and I combed Good Housekeeping for tips to better the ambience for my family and guests. However, it wasn’t until I moved to Paris that I discovered how little I knew about what truly makes a pleasurable dining experience.

Driving In France

Nervously, I edged into traffic and was, within a few minutes of breath-holding, relieved by the minor miracle of finding a free parking space in front of a cafe. I sat down with my iPhone to map a plan for the week.

In search of sun and warmth, my idea was to head for the Mediterranean beaches but was told it would be very crowded in July, and the distance seemed too far – 8 hours on expensive autoroutes. So I convinced myself to keep it simple on the first day and headed to Beaune, the "wine capital of Burgundy," less than two hours away by toll road.

What is land? Land can have many different meanings. Land can mean wealth, profit, prosperity, privilege, prestige, power, control, status, accomplishment, satisfaction, success, fame, respect, honor, dignity, safety, security, stability, continuity, contentment, freedom, happiness, hope, joy, beauty, love...

Land, for most people of the world, means wealth. Wealth, like beauty and love, is in the eye of the beholder.

Mama Arli’s Due Date

“Na! Na! Hurry; let’s go to the market! Ayo!” Mama Arli’s raspy voice bellows below my kitchen window.

Mama Arli is my neighbor four houses down from mine, and she is always yelling at me. She’s pregnant with her third child, though hardly showing. Arli is the name of her firstborn son, and his name replaced her own once he was born. All mothers are called by their firstborn’s name without exception.

Her house is sturdy, also on stilts, and she is fortunate to have a deep well located just a few feet from her kitchen ladder. It is November in Indonesia and this means its coffee-picking season for those in our Sumatran village. Mama Arli and her husband aren’t home much; instead they are occupied with the daily task of harvesting beans, and then drying the beans on tarps beside their home.

In the mid-90s, I was living and working as an ESL teacher at a private school in Kanazawa, Japan, a couple of hours by train from my relatives living in Kobe. I liked to visit them at least once a month to get to know them and stave off homesickness. The train ticket usually cost about $150. Sometimes I took the bus to save money, even though it was a much longer trip.

One day, our office boy, Kazu (who also worked part-time for a travel agency) told me that he could get me a free ticket to Kobe that weekend. He was booking a chartered bus which had an empty seat. The only catch, he explained, was "Overnight bus. Maybe you be tired." I said sure, that would be fine, "I can sleep on the bus." He gave me a quizzical look and said, "Ahhh...no sleep." As a foreigner, I was by then used to getting quizzical looks from the locals, so I didn't comment or think much about his hesitation.

When the weekend came, my boss and his wife offered to drive me to the bus station. "So, Kazu got you on the overnight bus. Have you ever taken overnight bus before? You might be too tired when you get there." I said that I had taken other overnight buses and I could always fall asleep. "Hm. I guess you won't sleep," my boss said. I assumed he figured it would be too uncomfortable, so again I said nothing.

They dropped me off and said, smirking, "Okaaaay...have a nice trip. Let me know how you sleep." In retrospect, I should have wondered why they were smirking.

Christmas in Kyoto did not sound promising but the flight was cheap. Having spent the last several Christmases huddled around the small wooden tables of the German Weihnachtsmarken, hands wrapped tightly around steaming ceramic mugs of glühwein, we expected Japan to be a bit of a disappointment in terms of holiday spirit.

There would be no Christmas markets selling roasted sausages or over-sized steins of altbier. There would be no outdoor festival tables to provide the inevitable camaraderie that accompanies the mass consumption of mulled wine in freezing temperatures. Communication would be near impossible as both my wife Lauren and I spoke very little Japanese and could not read kanji or katakana.

Nonetheless, one evening as we approached the bottom of our second bottle of wine, we decided Kyoto would make for a fine introduction to Japanese culture, with the added bonus of seeing drunken Japanese “salary men” stumbling around in Santa hats.

Inside Jamaica’s Blue Mountains: A Stranger in their Midst

The ancient Land Rover banged through another pothole as the rain poured onto the muddy, treacherous road. “We’re almost there,” my husband shouted encouragingly. I nodded, and clutched the door handle even tighter. Our little baby, carsick, had already thrown up twice. Driving from Kingston up 4000 feet into Jamaica’s Blue Mountains, with precipitous drops just steps away, frightened me into speechlessness. When the vehicle’s tires slipped at a hairpin turn, I silently begged God to keep us safe.

Hamer woman, Ethiopia. Photo by Michael Lorentz/Safarious.com

We pull up the Land Cruiser next to a petite man walking along the road. He is wearing a sarong-type skirt; his hair is coiffed in mud and feathers. He is distinguished.

“It is Wolle!” cries Mageru as he gets out from behind the wheel. “He is the Chief of Chiefs for the Hamer people.”

They greet each other in the traditional way for Ethiopian men – clasping each other’s backs with the left hand, shaking right hands while butting right shoulders three times. Wolle’s head feathers stroked Mageru’s mustache.

In the Hamer language, Mageru introduces me as his wife. Wolle looks me over and absent-mindedly undoes and reties his sarong. He wears nothing underneath.

“We should invite him to camp with us,” suggests Mageru. “It is a long way back to his village.”

Wolle is happy to do that but insists on supplying dinner and so we swing the car off the road and bump our way across the scrubby, dry savannah. A landscape so formless, I cannot gauge how many miles we have travelled before reaching Wolle’s family enclave, a few cone-shaped huts made of sticks and grass and encircled by thorn bushes.

As I get out of the car, I am immediately surrounded by dozens of naked children and, standing back, shy semi-naked women. The women and I smile uncertainly – not knowing what is expected of us.

Meanwhile, under Wolle’s direction, Mageru and a few other men are playing chase with a small goat. The goat loses, and is manipulated safely - but not quietly - into the back of the Land Cruiser. He is wedged in tight and I pray that he will not pee, poo or upchuck on our gear.

It surely is the goat’s first car ride and it will definitely be his last. And by the time he bleats all the way back to our campsite, I am not feeling even a smidge remorseful. Our cook hustles him off (out of sight of my tender ferenj sensitivities) and disposes of him quickly; within a few hours he has become a tasty stew called figel wot. It is a pleasant camping evening; the men’s Amharic/Hamer murmurings around the fire are like soft ambient music to ears that don’t understand.