BE INSPIRED BY TRANSFORMATIVE TRAVEL EXPERIENCES

Whether it's subtle shifts in attitudes or life-altering realizations, our transformative travel stories share ah-ha insights and experiences.

Featured

Join Ellen Barone on a Scottish adventure. From the ancient charm of Edinburgh to the coastal haven of Charlestown, her journey unfolds tales of warmth, unexpected friendships, and the timeless allure of Scotland. This is more than a travelogue; it's a love affair with a place that becomes a cherished second home.

Nature-lover Bindu Gopal Rao shares her transformative journey from expecting too much from a wildlife safari to finding joy in the unexpected. Her heartwarming story serves as a reminder that the true beauty of the wild lies in embracing its unpredictability.

Join Noor Anand Chawla on a powerful exploration of self-empowerment and the celebration of individuality as she explores the transformative impact of Indian art, challenging conventional beauty ideals and inspiring a new perspective on self-worth.

When Elyn Aviva and her husband traveled to Ireland to walk Brigid’s Way Celtic Pilgrimage, nothing went as planned. A friend who agreed to meet them couldn’t. Hotel reservations were canceled. Car rides along country roads and unexpected encounters with friends supplanted long solitary walks in nature. Yet, the journey was every bit a pilgrimage.

Gary White created from imagination from an early age. From music composition to book writing and dowsing, he’s spent a lifetime traveling to that nameless place of connection where imagination resides and ideas are manifested. Join him on the journey.

Thirty-seven days into self-isolation Ellen Barone asked her husband Hank, “Are you lonely?” Like much of the world’s population, they are physical-distancing and staying home to help prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus COVID-19. Would this, she worried, lead to loneliness? And, in turn, to biological effects as deadly as the virus itself? Instead, isolation has brought clarity to something they’d innately suspected all along.

Elyn Aviva has spent more than half of her life going on, studying, or writing about pilgrimage—specifically, the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Today, as she adjusts to the disorientation of isolation, she poses the question: Could it be that like a pilgrimage, this pandemic offers an opportunity to journey inward and engage in deep self-exploration?

Perfect vacation spot. Check. Perfect partner. Check. So why did Stephanie Ambarsumyan feel anything but perfect? It was an important question and one that she hadn’t realized needed asking until she went away.

She’d shaved her head to experience life as a bald woman. Resigned a six-figure job to live in a rural Irish cottage. Given away all of her possessions. Twice. And then Tara Myers decided to do something really scary: apply for a Russian visa and go to St. Petersburg. Alone.

Richard Collins was at a low point in his life when friends decided he needed a night out at Healing House, a performance art center in Chiang Mai, Thailand. He arrived feeling resistant and awkward, but like life often does when you are at rock bottom; the experience surprised him.

Pamela Blair, in the Sudan on the final leg of a long train voyage over a hot and empty desert, had prepared herself to be bored. It was what she hadn't planned on, however, that would forever change the way she saw the world and herself in it.

In a world that seems to be spinning out of control, Ellen Barone is surprised to find that she is still full of hope. Like everyone else, she has moments of disgust and despair, but then, almost miraculously, a ray of light shines through. How does this happen? She blames it on travel.

A transformational hike in the mountains results in a profound emotional release for Nancy King, leaving her with a lingering sense of solace and clarity that had previously proved elusive.

For American expat, BJ Stolbov, one of the most interesting and informative things about living in the Philippines is observing cultural norms. In this insightful essay, BJ reflects on Filipino attitudes about looking foolish in public, a topic which he's very familiar with.

When B.J. Stolbov left the United States to live abroad, he knew no one and no one knew him. He chose to view this as an opportunity to shed the masks and roles and expectations of his past and focused on becoming the person he wanted to be. The result is a life of unexpected joy.

When twin sisters set off on a hiking adventure in the Grand Canyon, a shared fear of heights threatened to ruin the trip. Learn how the sisters made the powerful choice to hike beyond their fears in a decision inspired by the gentlest flutter of a butterfly's wings.

A visit to Arches National Park inspires this reflective essay on the powers that shape, pare, trim, and mold this unique region of the American Southwest and the relationship to how time molds our eroding bodies and identies.

by Dan Dworkin

To travel solo for days in a kayak is to be not on or in but of the water. It loves you, rocks you like your mother did, speaks to you with many voices, supports your meandering, bathes you, feeds you, tells you when to travel and when to stay still on the island of the moment. On every trip there is a time of storm, of being wind-bound when the judicious kayaker stays put, writes, rests, wanders, constructs stone sculptures and listens for the still, small voice.

by Dina Lyuber

Being naked in public, for a North American, is the stuff of nightmares. Why? Is it because our bodies are so embarrassing? Perhaps it’s just a social convention; we are expected to hide our bodies, and so we feel awkward in public spaces when we must expose them. Maybe this is why many tourists avoid bathhouses. After all, they have a perfectly nice, private bathtub in their hotel room. And back home, they can wear a bathing suite as they sink into the hot tub at the community pool.

They may have avoided exposure, but they have no idea what they are missing.

by Dan Dworkin

What would you do if you were asked to voluntarily give up your cell phone, computer, TV, and sex for a month? When I revisited my Peace Corps assignment after forty-two years away, the people of my village in Fiji, indeed the residents of the whole province, were doing just that, in a manner of speaking. They were giving up tobacco, yaqona (kava), their ceremonial drink, and sex for a month. Why would they do such a thing?

One hundred and forty years ago, the people of a nearby village, Nabutautau, killed and ate the Methodist Reverend Thomas Baker. When I visited in July, 2011 they were conducting a ceremony of reconciliation, begging the Methodist Church to forgive them for their ancestors' actions.

by Angela Smith Kirkman

As far back as I can remember, my life’s goal has been to travel around the world. Now, as I sit in row twenty-two of our Boeing 777, chasing the moon over the Pacific somewhere between Tokyo and the International Date Line, I can feel the book closing on this chapter, on the whole epic adventure. And the same question keeps resonating in the back of my mind.

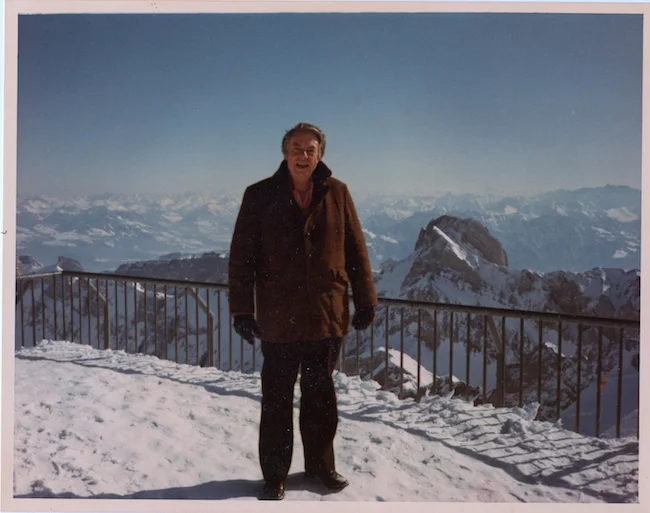

I was born with Fernweh, an ache to explore faraway places. It’s in my DNA; both of my parents had it. It was my dad, however, who taught us to pack adventure into our explorations.

Like my mother, I’d bask in the preparations for travel. I’d research, map out itineraries, and pack well in advance. For Daddy, however, the best part of travel was the adventure—the experiences you couldn’t plan for.

It was a gorgeous day for a hike--sunny, blue skies, comfortable temperature-perfect hiking weather. F suggested we hike up to the summit of the 12,000’ peak, taking our time, enjoying the profusion of wildflowers that had suddenly emerged after the night’s rain. She was used to hiking at lower altitudes, so we stopped whenever she needed to catch her breath or eat a snack. We climbed in companionable silence, finding the meandering path up to the top with no trouble.

Almost as soon as we started eating, it began to rain. We put on our rain gear, packed up our food, and started hiking down the mountain. The temperature dropped. Balls of hail mixed with the rain. Rivulets of water poured down what we thought was the trail.

Suddenly she screamed at me. “I’m not doing this anymore. Why do you always have to hike? Why can’t we ride bikes? This is dangerous!”

I was in the back of a truck bouncing through Port-Au-Prince with six strangers. We sat in complete silence as we drove past groups of children, their pleas for money blending into a steady drone of unintelligible noise as we passed. The only thing separating me from the Haiti I had heard so much about was a thin metal grate. Barely enough to keep the children from climbing in when we stopped, it only mildly interfered with my view of the city.

I expected to feel bad. I knew Haiti was the poorest country in the western hemisphere. I knew they had severe problems with deforestation and clean water. I thought when I arrived I would empathize or feel sad for them. Instead, I watched silently as we made our way through the streets, feeling only wonderment.

Little did I know that in a few days I would have the most shameful experience of my life.

The phone rang, a welcome break from correcting student essays. “Want to take a road trip to New Mexico?" asked my son. “I’ve got five days off and I haven’t seen you in a while.”

My son. The southwest. Five days of fun. "Of course," I replied.

I am sure you’ve heard that Spanish food is incredible, that it’s unlike anything you’ve ever tasted, that it’s innovative and bright and well, you know – all that hype. Here’s the thing. It’s totally true. Unfortunately, it took me a good two years of living in Spain to realize it.

Let me back up a bit. I moved to Spain on the premise of staying for nine months – just enough time to explore Europe and sink my teeth into Spain before heading back home. My first day in Spain, I was all alone. I hadn’t made friends yet, but that clearly had no effect on my hunger, and I walked into a little bar to order a sandwich. Now a sandwich in the United States is a hefty sort of thing, layered with ingredients and toppings and sauces. And as I was fairly hungry when I ordered this “sandwich,” I was more than disappointed when two flimsy toasted pieces of sandwich bread came my way with a little lettuce, tomato and a fried egg stuffed between them.

Okay, so my first experience wasn’t great, but over time I did learn to enjoy Spanish food. I liked it. I really liked it. But I never reached the point of loving it. I continued ordering the same things again and again at restaurants and bars, and never felt it was special. In my head, American food was superior to the simple and often bland food of Spain.

About a year and a half after I moved to Spain, I met my Spanish boyfriend, and I decided to tell him my opinion about all of this. He was shocked. I thought he was too proud to admit I was right, but I realize now I was horribly mistaken. As we continued dating, I started tasting foods I had never even heard of before, and I had to come to terms with the fact that after eighteen months of eating three meals a day, I actually knew nothing about Spanish food. Actually, my realization was an epiphany.

by Laura Marriott

My journey to Prague did not get off to an auspicious start. I arrived at Vaclav Havel airport in a little bubble of anxiousness, fleeing the wreck of a disastrous year. Multiple bereavements and family illnesses had made my final year of University more of a trial than a pleasure. Then, I was offered the opportunity to spend a month in Prague, much of it on my own; hopefully giving me time to recover in peace. First I was to attend a political sciences summer school at Charles University in Prague and then I had several weeks of nothing but the heat of my own company. The accommodation that I was staying in was painted in the industrial yellows and greens that are more often than not to be found in hospitals and forever carry with them an air of sickness. It was the cheapest and the worst accommodation I have ever stayed in. I hoped to spend as little time in it as possible.

When was the last time you took 3 slow, deep breaths? The stress of daily life keeps my breaths shallow, and my stomach tight. Although I'm semi –retired, I still lead a busy 21 st century westerner’s life. I drive in traffic, surf the net, fight to get to the checkout in Trader Joe’s, pay bills, pump my own gasoline, yech! This summer things just weren’t working in my life. I had a disappointing love affair, my friends were unable to keep social plans, I was lonely, stuck with a property I couldn't sell, two-and-a-half years into a self -imposed five year austerity program. When I became aware of how tight my stomach was, I decided to enroll in a 10 day silent meditation retreat at Vallecitos Mountain Ranch in New Mexico to avoid a future diagnosis of acid reflux.

When an old master artist like Di Vinci decided to paint over a part of his initial composition, it was called pentimento, which means to change your mind. Life is just like that; sometimes we paint a composition and then change our minds. Thus, we alter our lives. I went to meditate on order to look deeply into my life composition and alter what needed to be altered.

Set in a pristine mountain forest 9,500 feet above sea level, Vallecitos has nine ponds, flowered valleys, an old restored hunting lodge and private cabins for participants. I joined about 37 like-minded people from various parts of the U.S. and two teachers to explore 10 days of being with my own thoughts, feelings and sensations. Here are some of the awareness’ I garnered.

Living in a foreign country is an opportunity to learn about a different culture, a different way of seeing and responding to the world. It provides an opportunity to immerse yourself in new customs and traditions, and to see what really matters and is important to people around the world. It is also an opportunity to examine, from a distance, your own customs and traditions and, most important, your own cultural assumptions.

“So, when exactly are you coming home?” my father asked.

“I don’t know, Dad. Our visas allow us to stay in Peru for at least three months, then we’re thinking of heading on to Argentina and Chile...”

The broken and sputtering magicJack connection at the South American Explorers Club in Cusco broadcasted about every third word of our conversation, but the message that traveled down the steep stone streets of the ancient Inca capital and across the continents to the lush green lawns of Newark, Delaware, the college town I’d grown up in and where my parents still live, was crystal clear: We weren’t coming “home”.

The truth was, my husband, Hank, and I had no idea when, or if, we were going home. We didn’t even know what “home” meant anymore. We’d been winging it, temporarily inhabiting Mexico, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Peru: itinerant and loose in the world in a manner that both worried and intrigued family and friends back home.

We were four thousand miles from our homeland, eleven thousand feet above sea level, south of the Equator where summer is winter, and living in a fourth-floor walkup without heat. Yet, life felt sweet and rich and fortunate.